Manufyn helps validate tolerances before they inflate cost.

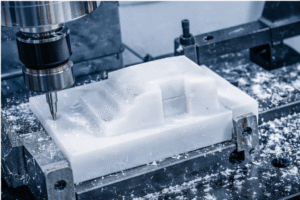

CNC tolerances define how closely a machined part must match its nominal dimensions. Because machining involves tool wear, thermal expansion, and spindle movement, no CNC process produces perfect geometry. Tolerances quantify the acceptable variation so parts remain functional, reliable, and repeatable.

Proper tolerance selection improves assembly fit, reduces rework, and ensures consistency across suppliers. However, tightening tolerances everywhere increases machining time, inspection cost, and scrap rates. Therefore, engineers must balance precision with manufacturability.

This guide provides a concise, engineering-focused overview of how CNC tolerances work and how to apply them effectively. It covers tolerance types, realistic machining capability, stack-up principles, and best practices for technical drawings.

Manufyn verifies tolerance feasibility during quoting, ensuring your RFQ reaches only suppliers capable of meeting the required accuracy.

What Are CNC Tolerances?

CNC tolerances define the acceptable dimensional variation around a nominal value. For example, a dimension of 50.00 mm ±0.05 mm allows a part to measure between 49.95 mm and 50.05 mm. This range accounts for real-world machining variation, which happens even under ideal conditions.

1. Why Machining Cannot Produce Perfect Geometry

Every machining process has inherent sources of variation. These include tool wear, heat buildup, spindle movement, material stress relief, and fixture vibration. Because these factors change during production, tolerances ensure the part remains functional despite these variations.

2. Why CNC Machining Requires Defined Tolerance Bands

When tolerances are not defined, machinists rely on general shop defaults. In many cases, these defaults are too loose for functional features and unnecessarily tight for cosmetic areas. Specifying tolerance bands eliminates confusion and reduces rework during inspection.

3. Impact of Tight vs. Standard Tolerances

Tight tolerances reduce flexibility in machining. They typically require slower feeds, smaller step-downs, and additional finishing passes. As a result, cost increases rapidly below ±0.05 mm. Ultra-tight tolerances often need secondary processes such as reaming, honing, grinding, or precision boring.

Because machining difficulty rises exponentially, tolerances should only be tightened where function demands it. This approach ensures stable production quality while keeping cost under control.

Get a tolerance-focused DFM review before machining.

Upload your CAD and drawing on Manufyn to receive engineering feedback within 24 hours, including feasibility checks and cost-saving tolerance recommendations.

Types of Machining Tolerances

Machining tolerances define how individual features must be controlled during CNC production. Each type serves a different engineering purpose. Choosing the right type ensures the part meets its functional, assembly, and inspection requirements.

Below are the primary categories used in CNC design and engineering drawings.

1. Linear Tolerances

Linear tolerances apply to straight-line dimensions such as length, width, thickness, and diameter. They are the most common form of tolerancing in CNC machining. For example, ±0.10 mm is typical for non-critical features, while ±0.02 mm is used for precision fits.

Linear tolerances are easy to inspect with calipers, micrometers, or CMMs. Because of this, they serve as the baseline for most CNC feature control.

2. Angular Tolerances

Angular tolerances define how accurately a feature must meet its intended angle. They are essential for chamfers, angled faces, countersinks, or draft surfaces.

For example, a 45° chamfer with ±1° tolerance is common. However, precision mechanisms may require ±0.2° or tighter. These tolerances matter because even a small angular deviation can shift the location of mating surfaces.

3. Bilateral vs. Unilateral Tolerances

Bilateral tolerances allow variation in both directions. Example: 20.00 mm ±0.05 mm. This approach offers predictable machining since tools are not forced toward one side of the limit.

Unilateral tolerances allow variation only in one direction. Example: 20.00 mm +0.10 / -0.00 mm. These are used when a minimum or maximum dimension must be protected, such as clearance fits or press-fit features.

Because unilateral tolerances restrict tool compensation, they increase machining difficulty. They should be used only when function requires them.

4. Geometric Tolerances (GD&T)

Geometric Dimensioning and Tolerancing (GD&T) controls a feature’s form, orientation, profile, and location. GD&T ensures that parts assembled across different batches remain consistently aligned.

Common categories include:

Form Tolerances

- Flatness

- Straightness

- Circularity

- Cylindricity

These control the shape of a single feature without referencing another.

Orientation Tolerances

- Perpendicularity

- Parallelism

- Angularity

These control the tilt or alignment relative to a datum.

Location Tolerances

- True position

- Concentricity

- Symmetry

These define how accurately features must align to datums or to each other.

Profile Tolerances

- Profile of a surface

- Profile of a line

These control complex curves, freeform surfaces, and 3D contours.

GD&T is powerful but must be used intentionally. Overusing it increases machining and inspection complexity without adding value.

5. Choosing the Right Tolerance Type

Use linear tolerances for size control, GD&T for relational accuracy, and angular tolerances when orientation matters. In early design stages, favor simple linear tolerances. Introduce geometric tolerances only when the functional relationship between features requires it.

CNC Machine Tolerance Capability

A CNC machine’s tolerance capability depends on its rigidity, spindle quality, axis calibration, and thermal stability. It also depends on material choice and feature geometry. Engineers must understand realistic tolerance ranges before assigning tight tolerances on drawings.

This section outlines typical tolerance bands used in production machining.

1. Standard Machining Tolerances

Most CNC machines can reliably achieve ±0.10 mm for general features. This range is suitable for outer profiles, bracket shapes, lightly loaded housings, and cosmetic surfaces. Standard tolerances are also ideal for prototypes where functional relationships are not tight.

2. Precision Tolerance Ranges

Precision tolerances typically fall between ±0.02 mm and ±0.05 mm. These values are used for mating surfaces, hole diameters, sliding fits, and functional alignment features.

Achieving this range often requires slower machining, stable fixturing, and additional finishing passes. As a result, cost increases compared to standard machining.

3. High-Precision and Ultra-Tight Tolerances

Tolerances tighter than ±0.01 mm enter the high-precision domain. Achieving them often requires:

- Climate-controlled machining environments

- Specialized spindles

- Multiple finishing passes

- High-stability fixtures

- Secondary processes like grinding or honing

Ultra-tight tolerances are typically found in aerospace, medical devices, metrology equipment, and high-precision robotics.

Because they add significant cost and complexity, they should only be specified when function mandates them.

4. Material-Based Tolerance Expectations

Different materials support different tolerance levels due to their machining behavior.

- Aluminum: Excellent machinability; stable at tight tolerance ranges.

- Stainless Steel: Higher cutting forces require slightly looser tolerance expectations.

- Brass/Copper: Very stable; suitable for precision machining.

- Titanium: Poor thermal conductivity makes tolerances harder to maintain.

- Plastics: Heat sensitivity and flexibility require generous tolerances to avoid warping.

Therefore, tolerance decisions should always factor in material behavior.

5. Process-Based Variation

Tolerance capability also depends on the CNC process:

- CNC Milling: Stable for most dimensions but less tolerant of deep or narrow features.

- CNC Turning: Produces very tight diametral tolerances thanks to axis symmetry.

- 5-Axis Machining: Excellent for multi-face accuracy and reduced setup errors.

- Secondary Operations: Reaming, boring, honing, and grinding achieve the tightest tolerances.

Each process has strengths, so engineers should choose according to functional requirements.

Match your tolerance requirements with the right manufacturer.

Manufyn routes your RFQ only to suppliers proven to meet your specified CNC tolerances, ensuring accuracy from prototype to production.

Machining Tolerance Chart

A machining tolerance chart provides quick reference values for standard, precision, and high-precision ranges. These ranges help engineers choose tolerance bands that align with real machining capability. Using a chart early in the design process also prevents over-tolerancing and reduces unnecessary manufacturing cost.

The table below summarizes typical CNC tolerance classes for metal and plastic components. These values represent realistic capabilities for modern 3-axis, 4-axis, and 5-axis CNC machines under stable cutting conditions.

Standard CNC Tolerance Ranges

Standard tolerances apply to most non-critical features. They provide a balance between manufacturability and dimensional accuracy.

| Tolerance Class | Typical Range | Suitable For |

|---|---|---|

| General machining | ±0.10 – ±0.20 mm | Outer profiles, brackets, covers |

| Standard holes | ±0.10 mm | Clearance holes, non-critical bores |

| Flatness | 0.1 – 0.2 mm | Enclosures and plates |

| Position | ±0.20 mm | Non-critical alignment features |

These values work well for prototypes and general engineering parts where functional relationships are not extremely tight.

Precision CNC Tolerance Ranges

Precision tolerances offer improved fit and functional stability. They are used for mating parts and assembly-critical geometry.

| Feature | Precision Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Diameters | ±0.02 – ±0.05 mm | Ideal for shafts and bores |

| Flatness | <0.05 mm | Requires controlled machining |

| Position tolerance | ±0.05 – ±0.10 mm | Suitable for bolt patterns |

| Angular features | ±0.2° | Used for chamfers and draft faces |

Precision tolerances often require slower feeds, improved fixturing, and additional finishing passes.

High-Precision and Ultra-Tight Tolerances

Ultra-tight tolerances are used only when design function demands extreme accuracy. Aligning with this range dramatically increases machining cost, cycle time, and inspection effort.

| Feature | High-Precision Range | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Bore diameters | ±0.005 – ±0.01 mm | Bearings, precision fits |

| Flatness | <0.02 mm | Sealing faces |

| Position | <0.02 mm | Optical mounts, robotic systems |

| Surface profile | <0.01 mm | Complex freeform surfaces |

These tolerances are typically achieved in temperature-controlled environments or through secondary operations such as honing or grinding.

Why a Machining Tolerance Chart Matters

A tolerance chart offers several advantages:

- It reduces guesswork during design.

- It prevents unnecessary precision.

- It aligns engineering expectations with real manufacturing capability.

- It ensures suppliers understand tolerance intent clearly.

Using this chart as a baseline helps engineers build consistent tolerance standards across product families and suppliers.

Factors That Influence Achievable Tolerances

Even with advanced CNC equipment, tolerance capability depends on several physical, mechanical, and thermal factors. Understanding these variables helps designers avoid specifying unrealistic or overly tight tolerances.

Below are the primary elements that influence tolerance accuracy during machining.

1. Tool Wear and Cutting Edge Condition

Cutting tools wear down as they remove material. As wear increases, the tool diameter changes, and dimensional accuracy decreases. Tool wear also generates additional heat, which expands the tool and affects size control.

Because of this, features requiring tight tolerances may need:

- Fresh tools

- Slower feed rates

- Reduced stepovers

- Finishing passes

Tool wear is one of the largest contributors to tolerance drift in production machining.

2. Tool Deflection and Rigidity

When tools extend deep into a pocket or bore, they deflect under cutting loads. Even a small deflection can shift a dimension by several microns. Deflection becomes more severe with:

- Long-reach tools

- Small-diameter end mills

- Harder materials

- Deep cavities

- Side-loaded toolpaths

To maintain tolerance accuracy, designers should avoid extreme depth-to-diameter ratios or allow larger corner radii.

3. Machine Calibration and Thermal Stability

CNC machines expand slightly as they heat up during operation. Spindles, slides, ballscrews, and structural components all experience thermal growth. Even controlled environments see small positional errors throughout a long machining cycle.

Well-calibrated CNC machines can compensate for some thermal drift, but not all of it. As a result, the tighter the tolerance, the more sensitive the process becomes to heat.

4. Fixturing Stability and Clamping Strategy

A part must remain perfectly secure during machining. Any vibration or micro-movement at the fixture affects dimensional accuracy and surface finish. Thin-walled or flexible parts are more prone to instability.

Good fixturing improves:

- Dimensional repeatability

- Surface quality

- Positional accuracy

- Flatness and parallelism

Designers should consider how easily a part can be held during machining when assigning tolerances.

5. Material Machinability and Thermal Behavior

Materials vary significantly in how they respond to machining forces. For example:

- Aluminum: stable, predictable tolerances

- Brass: excellent precision capability

- Stainless steel: higher cutting forces cause deflection

- Titanium: retains heat, amplifying tolerance drift

- Plastics: expand, contract, and warp with temperature changes

Because plastics deform under heat, they require generous tolerances relative to metals.

6. Cutting Strategy and Toolpath Planning

Machinists adjust toolpaths to balance accuracy and efficiency. Finishing passes, climb milling, adaptive clearing, and constant-engagement strategies help maintain tolerances. However, these methods increase cycle time.

For tight tolerances, machinists may need to:

- Reduce feed rate

- Minimize tool engagement

- Use specialized cutters

- Program multiple semi-finish passes

These adjustments add time and cost, which is why tolerance decisions must align with functional requirements.

Engineering Guidelines for Selecting CNC Tolerances

Selecting the right CNC tolerances is a balance between functional performance and manufacturability. Overly tight tolerances increase machining cost and inspection difficulty, while loose tolerances lead to poor fit and unreliable assemblies. The guidelines below help engineers define tolerances that are realistic, efficient, and aligned with production capability.

1. Identify Critical-to-Function Features

Not every dimension matters equally. Start by separating functional features from non-critical ones. This ensures tight tolerances are reserved only for the areas that need them.

Examples of critical features include:

- Shaft diameters

- Bearing bores

- Alignment bosses

- O-ring grooves

- Locating pins

- Sliding interfaces

These features directly impact how a part fits or functions. As a result, they deserve tighter tolerances and, when necessary, geometric controls.

Non-critical features include cosmetic surfaces, outer contours, and chamfers. These can follow standard machining tolerances without affecting performance.

2. Establish Datums and Reference Frames

Good datum strategy improves accuracy and repeatability. Datums define the reference surfaces from which all other dimensions are measured. They help machinists orient a part correctly during each setup.

A strong datum scheme:

- Reduces tolerance stacking

- Simplifies inspection

- Improves multi-setup consistency

- Ensures features relate correctly

For functional assemblies, datums should align with the part’s load paths, mounting surfaces, or mating edges.

3. Apply GD&T Strategically

Geometric tolerances (GD&T) help control form, orientation, and location. They are powerful, but they become costly if overused. Designers should apply GD&T only when positional or form accuracy truly matters.

Use GD&T when:

- Holes must align to a bolt pattern

- Rotating features need concentricity

- Faces must remain parallel for assembly

- Sliding components require consistent clearance

Avoid applying GD&T to cosmetic or non-functional surfaces. This keeps drawings clean and reduces manufacturing cost.

4. Choose Standard vs Tight Tolerance Bands

A good starting point is:

- ±0.10 mm for general features

- ±0.05 mm for semi-critical features

- ±0.02–0.05 mm for functional fits

- ±0.01 mm and below only for critical assemblies

This tiered approach keeps machining efficient while protecting functional intent.

5. Understand How Tight Tolerances Affect Machining Time

Tighter tolerances reduce allowable variation. As a result, machinists must adjust toolpaths and cutting parameters carefully. This typically requires:

- Slower feed rates

- Reduced depth of cut

- Multiple finishing passes

- Specialized tools

- Extra inspection steps

Because of this, cost rises rapidly below ±0.05 mm. Engineers should tighten tolerances only when necessary to support function.

6. Align Tolerances with Inspection Capability

A tolerance is only useful if it can be measured accurately. Certain tolerances require CMMs, gauges, or micron-level instruments. If inspection cannot verify a tolerance, the specification becomes meaningless.

Therefore, engineers should collaborate with manufacturing teams to ensure inspection methods match the required accuracy.

Manufyn’s engineering review flags tolerance risks before production. This includes identifying over-constrained features, unrealistic ± values, and missing GD&T. You receive manufacturability feedback within 24 hours, ensuring your part is ready for efficient CNC machining.

Start your tolerance-critical machining project.

Share your files to receive a fast, accurate quotation from vetted CNC suppliers with verified precision capability.

Tolerance Stack-Up Analysis

Tolerance stack-up analysis evaluates how dimensional variations accumulate across multiple features. Even when each feature is within tolerance individually, the combined effect may exceed functional limits. Understanding stack-up is essential for assemblies, enclosures, and alignment-critical components.

1. Why Stack-Up Matters

Stack-ups determine whether drilled holes align, whether covers meet flat surfaces, and whether shafts seat correctly. Poor stack-up control leads to assembly failure, misalignment, or interference. As a result, designers must analyze tolerance accumulation early in the design phase.

2. Worst-Case Method

The worst-case approach adds the maximum possible variation from each feature. It represents the most conservative result and ensures 100% interchangeability.

For example:

If four dimensions each have a tolerance of ±0.10 mm, the total possible variation is ±0.40 mm.

This method is suitable for:

- Aerospace components

- Medical devices

- Safety-critical assemblies

However, it often results in unnecessarily tight tolerances.

3. Statistical (Root Sum Square) Method

The Root Sum Square (RSS) method assumes that variations behave statistically rather than add linearly. It calculates the combined tolerance as:

Total Variation=(T1)2+(T2)2+(T3)2+…text{Total Variation} = sqrt{(T_1)^2 + (T_2)^2 + (T_3)^2 + …}Total Variation=(T1)2+(T2)2+(T3)2+…

For the same four features at ±0.10 mm:

(0.12+0.12+0.12+0.12)=0.20 mmsqrt{(0.1^2 + 0.1^2 + 0.1^2 + 0.1^2)} = 0.20text{ mm}(0.12+0.12+0.12+0.12)=0.20 mm

RSS reflects real-world behavior more accurately than worst-case analysis. It is ideal for high-volume production where statistical variation applies.

4. Monte Carlo Simulation

Monte Carlo methods simulate thousands of tolerance outcomes using probability distributions. This provides the most realistic estimate of how assemblies behave under production variation.

It is valuable for:

- Complex assemblies

- Gear trains

- Robotics components

- Precision motion systems

However, it requires specialized software and is used mainly by advanced engineering teams.

Real-World Examples

1. Enclosures

Lid alignment depends on summed tolerances across multiple faces.

2.Gearbox housings

Bearing bores must remain aligned across multiple machined surfaces.

3.Electronics housings

Stack-up determines whether PCB holes align with standoffs.

4. Optical mounts

Positional errors accumulate rapidly and affect beam alignment.

Understanding these scenarios helps ensure tolerances support functional accuracy.

When to Use Tight Tolerances

Tight tolerances add machining complexity, but they are essential for features that directly affect function, alignment, or long-term performance. Engineers should apply tight tolerances selectively and only when the design requires high precision.

Below are the situations where tighter tolerance bands are necessary.

1. Interference Fits and Press Fits

Press-fit and interference-fit components depend on precise dimensional control. Even small deviations can change the amount of interference, which affects assembly force, load capacity, and long-term wear.

Examples include:

- Bearings pressed into housings

- Bushings and sleeves

- Dowel pins

- Couplings and hubs

These features typically require tolerances in the ±0.01–±0.02 mm range. Because the fit controls structural stability, precision is mandatory.

2. Precision Motion Components

Sliding, rotating, and linear-motion systems demand consistent clearance. Tight tolerances ensure smooth operation without excessive friction.

Common examples include:

- Linear guide block interfaces

- Actuator housings

- Gearbox components

- Shafts and rollers

In these systems, dimensional error accumulates quickly. Therefore, tolerance control is critical.

3. Alignment-Critical Geometry

When multiple features must align precisely, geometric tolerances help keep everything in place. Misalignment can cause functional failure even if individual dimensions are correct.

Alignment-critical features include:

- Bolt hole patterns

- Mating flanges

- Optical mounts

- Brackets that interface with sensors or actuators

True position, perpendicularity, and concentricity are often required in these cases.

4. Sealing Surfaces

O-ring grooves and gasket interfaces depend on accurate geometry to maintain a reliable seal. Even slight deviations can result in leaks or uneven compression.

Typical tight controls include:

- Groove depth tolerance

- Surface flatness

- Parallelism between sealing faces

These features often require both dimensional and geometric tolerancing.

5. High-Speed or Load-Bearing Interfaces

Components under high mechanical loads or rotational speeds require tight control to prevent vibration, imbalance, or premature failure.

Examples:

- Balancing surfaces

- Rotors and impellers

- Load-bearing frames

- Assembly interfaces with high structural demand

Because the forces are significant, precision ensures predictable performance.

Ensure tolerance stability across batches.

Manufyn monitors dimensional accuracy throughout production, helping you maintain consistent quality for recurring or large-volume orders.

When to Avoid Tight Tolerances

Not all features benefit from precision. Over-tolerancing leads to increased machining time, unnecessary inspection steps, and higher cost—without improving function. Engineers should avoid tight tolerances whenever they offer no practical advantage.

Below are scenarios where standard tolerances are preferable.

1. Cosmetic or Non-Functional Surfaces

Surfaces that serve primarily aesthetic or protective roles seldom require precision. Tightening tolerances on cosmetic faces only increases machining cost.

Examples include:

- Exterior faces of enclosures

- Logo or branding surfaces

- Decorative chamfers

- Non-contact edges

These features perform the same regardless of whether they are ±0.1 mm or ±0.3 mm.

2. Large or Flexible Components

Large plates, long beams, and thin-walled structures tend to warp slightly during machining. Holding tight tolerances on these parts can be unrealistic.

As a result, standard ranges are recommended for:

- Long extruded components

- Thin sheet-like parts

- Large flat enclosures

Trying to force these into ±0.02 mm tolerances will lead to repeatability issues.

3. Deep Pockets or Narrow Features

Deep, narrow pockets impose cutting challenges such as tool deflection and vibration. Tight tolerances inside these features significantly increase machining time.

Examples where looser tolerances are advised:

- Pockets deeper than 4× tool diameter

- Tall ribs

- Narrow internal channels

- Thin internal walls

Relaxed tolerances improve efficiency without hurting part performance.

4. Plastic Components

Plastics expand and contract more than metals. They also deform under heat, especially during deep cuts. Attempting ±0.02 mm tolerances in plastic parts often results in unstable dimensions.

Materials requiring looser tolerances include:

- ABS

- Nylon

- Polycarbonate

- POM (Delrin)

- Acrylic

Engineers should use wider tolerance bands to accommodate material behavior.

5. Non-Mating or Isolated Features

Features that do not interact with other components do not benefit from precision. Examples include:

- Outer contours

- Isolated bosses

- Decorative pockets

- Standalone slots

Applying tight tolerances here increases cost without improving functionality

How to Communicate Tolerances on Technical Drawings

Communicating tolerances clearly on a technical drawing ensures that machinists, programmers, and inspectors interpret design intent accurately. A 3D model defines geometry, but the drawing defines the rules for how that geometry must be produced and measured. Without clear tolerancing, manufacturers may rely on internal defaults that do not match functional requirements.

1. Use a Clear and Consistent Title Block

The title block should specify general tolerance values for all unspecified dimensions. This prevents ambiguity and reduces the amount of manual annotation needed on the drawing.

Most engineering organizations define default tolerance bands based on the number of decimal places. For example:

- X.X ±0.2 mm

- X.XX ±0.1 mm

- X.XXX ±0.05 mm

If you are using ISO 2768, list the tolerance class (e.g., ISO 2768-m).

This ensures that machinists apply consistent rules across the entire drawing.

2. Identify Critical-to-Function Features Clearly

Not all dimensions require tight control. Highlight critical features using:

- Bold outlines

- Labels such as “CRITICAL DIMENSION”

- Feature control frames (GD&T)

- Explicit tolerance callouts

- Datum references

By isolating key dimensions, you help machinists prioritize accuracy where it matters most and maintain efficiency where precision is not required.

3. Use GD&T Thoughtfully

GD&T should be applied only where geometric relationships matter. For example:

- Position for hole patterns

- Perpendicularity for mounting faces

- Concentricity for bores and shafts

- Flatness for sealing surfaces

Avoid “blanketing” drawings with unnecessary GD&T symbols. Overuse complicates inspection and inflates machining cost without adding functional benefit.

4. Avoid Redundant or Conflicting Dimensions

Repeated or redundant dimensions create confusion. Designers should ensure:

- Every critical feature has ONE controlling dimension

- Dimensions flow logically from primary datums

- Unnecessary edges or cosmetic features are not referenced

- Symmetry is noted rather than dimensioned twice

A well-structured drawing reduces interpretation errors and speeds up machining and inspection.

5. Include Functional Measurement Notes

Sometimes specific inspection methods must be followed. Include notes such as:

- “Inspect with CMM”

- “Measure after anodizing”

- “Do not measure burrs”

- “Break sharp edges 0.2–0.4 mm”

These notes ensure consistency across all suppliers and batches.

6. Provide 3D Models with the Drawing

While the 2D drawing defines tolerances, the 3D model defines geometry. Providing both ensures:

- Clear interpretation of complex surfaces

- Accurate CAM programming

- Reduced risk of misalignment between design intent and machining

Both files together close the loop between design, machining, and inspection.

Tolerances by CNC Process Type

A process-capability table helps engineers quickly understand what each CNC method can realistically achieve. This improves tolerance selection and ensures manufacturing expectations are aligned across suppliers.

CNC Process Tolerance Capability Table

| CNC Process | Typical Tolerances Achievable | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-Axis CNC Milling | • Std: ±0.10–0.20 mm • Prec: ±0.02–0.05 mm • High-Prec: ±0.005–0.02 mm |

Prismatic parts, pockets, slots, surface milling | Deep pockets, thin walls increase tool deflection |

| 4-Axis CNC Milling | • ±0.01–0.05 mm on multi-face features | Rotational surfaces, angled features, reduced setups | Long tool reaches can reduce precision |

| 5-Axis CNC Machining | • ±0.01–0.03 mm on multi-side features • Excellent angular accuracy |

Complex geometry, contoured surfaces, reduced stack-up | Higher machine/programming cost |

| CNC Turning (Lathe) | • Std: ±0.02 mm • Prec: ±0.005–0.01 mm • Excellent roundness |

Shafts, pins, bushings, threads | Non-cylindrical features require milling |

| Reaming | • ±0.005–0.015 mm hole accuracy • Smooth bore finish |

Tight-tolerance holes, precision fits | Only for internal circular features |

| Boring | • Positional accuracy • ±0.01 mm or better |

Precision bores in steel/aluminum | Slower, requires rigid setup |

| Honing | • Micron-level cylindricity • Excellent surface finish |

Hydraulic components, bearing bores | Only improves internal surfaces |

| Grinding | • ±0.002–0.005 mm • Exceptional surface quality |

Hardened metals, tooling components | Higher cost; temperature-sensitive |

Process Selection Guidelines

| Requirement | Recommended Process |

|---|---|

| Tight cylindrical tolerances | CNC Turning / Grinding |

| Hole accuracy better than ±0.02 mm | Reaming / Boring |

| Multi-face alignment accuracy | 5-Axis CNC |

| Deep pockets | 3-Axis with finishing passes |

| Ultra-smooth internal bores | Honing |

| Complex contoured surfaces | 5-Axis CNC |

Notes for Engineers

- Turning provides the tightest and most repeatable diametral tolerances.

- Milling tolerances degrade with tool reach, pocket depth, and tool diameter.

- 5-axis machining reduces setup-related error, improving positional accuracy.

- Secondary operations like reaming or honing are required for ultra-tight tolerance bores.

- Grinding delivers the highest precision, especially for hardened steels.

How Manufyn Ensures Reliable CNC Tolerance Production

Manufyn ensures tolerance-critical parts are machined accurately by matching your RFQ with suppliers that have proven capability in the required tolerance range, material type, and inspection equipment. Before machining begins, your drawings and models undergo a quick DFM review to validate tolerance values, identify over-constrained features, and highlight any GD&T or datum improvements needed for stable production.

During manufacturing, suppliers follow controlled setup strategies and use appropriate inspection methods—including CMM or gauge-based verification—for all critical dimensions. Manufyn monitors accuracy across prototypes and repeat batches, ensuring consistent tolerance performance throughout the entire production cycle.

Key Takeaways

CNC tolerances ensure that machined parts remain functional, reliable, and consistent across production. Selecting the right tolerance values requires understanding machining capability, material behavior, tool dynamics, and inspection methods. Over-tightening tolerances increases cost and complexity, while well-balanced tolerances improve both manufacturability and performance.

Engineers should classify features by function, choose datums carefully, apply GD&T only where needed, and validate tolerance stack-up early in the design process. Clear drawings and realistic tolerance bands help manufacturers produce parts efficiently and accurately.

Manufyn strengthens this workflow through tolerance-based supplier matching, engineering DFM support, and controlled inspection alignment. This ensures your parts meet the required precision across prototypes and production.

Bring your tolerance-critical parts to production with confidence.

Upload your CAD model and technical drawing on Manufyn to receive a verified manufacturing plan, precise quotations, and supplier matching tailored to your CNC tolerance requirements.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What tolerance can CNC machining typically achieve?

Most CNC machines hold ±0.10 mm for general features and ±0.02–0.05 mm for precision geometry. High-precision processes, such as grinding or honing, can achieve ±0.005–0.01 mm when the design requires extremely tight control.

Why do tight tolerances increase machining cost?

Tight tolerances require slower toolpaths, smaller stepovers, additional finishing passes, and more detailed inspection. As a result, machining time increases and more advanced measurement equipment is needed, raising both production and quality-control cost.

How do material properties affect tolerance accuracy?

Materials expand, contract, and react differently to cutting forces. Aluminum and brass support tight tolerances, while plastics and titanium are more sensitive to heat and vibration. Engineers should adjust tolerance bands based on each material’s machining behavior.

When should I use GD&T instead of simple ± tolerances?

Use GD&T when the relationship between features matters more than the absolute dimension. Position, flatness, perpendicularity, and concentricity controls are ideal for alignment-critical assemblies, hole patterns, and rotating components.

Do all CNC parts require a technical drawing?

No, but drawings are strongly recommended for any part involving tight tolerances, GD&T, special threads, surface finish requirements, or inspection instructions. Drawings eliminate ambiguity and ensure all suppliers interpret tolerances consistently.

How does tolerance stack-up affect assembled parts?

Small dimensional variations accumulate when multiple features interact. Without stack-up analysis, the final assembly may bind, misalign, or develop gaps. Evaluating worst-case or statistical stack-up early prevents functional issues after machining.