Manufyn helps you scale from prototype to production.

Injection Mold Venting Design Guideline

Mold venting is one of the least visible yet most critical elements of injection mold design.

When venting is engineered correctly, parts fill consistently, surface defects are minimized, and tooling runs with a wide, stable process window. When venting is overlooked or treated as a secondary tooling detail, manufacturers encounter short shots, burn marks, flash, high clamp forces, and repeated mold rework.

This Mold Venting Guide is written for:

- OEM engineers

- Product design teams

- Tooling and manufacturing managers

who need to validate venting decisions before tooling is finalized.

This mold venting guide focuses on:

- Engineering rules of thumb

- Material-specific venting metrics

- Geometry-driven vent placement logic

- When venting will solve defects vs when redesign is required

- How venting impacts cycle time, tooling cost, and production stability

The objective is simple:

Help you decide whether your part is vent-ready, toolable with risk, or requires design intervention — before steel is cut.

Throughout this guide, Manufyn’s tooling and DFM teams are referenced where venting decisions intersect with:

- CAD review

- Mold design

- Tool modification

- Production optimization

Why Mold Venting Is a Tooling-Critical Decision

Mold venting directly determines whether air and gases can escape the cavity at the same rate the molten polymer fills it. When this balance is not achieved, defects appear regardless of how much pressure, temperature, or clamp force is applied.

From a tooling standpoint, venting is one of the few design parameters that cannot be freely corrected after steel is cut. Unlike process settings, vent locations and vent depths are constrained by parting lines, inserts, and steel geometry. This makes venting a front-loaded engineering decision, not a trial-stage adjustment.

In production environments, poor venting is a primary contributor to:

- Unstable filling behavior

- Narrow process windows

- Higher scrap during ramp-up

- Increased tooling maintenance over time

These issues compound as production volume increases, turning what appears to be a minor tooling oversight into a long-term manufacturing liability.

How poor venting shows up in real molds

When venting is inadequate, the effects are rarely subtle. They tend to appear repeatedly at predictable locations and worsen as injection speed or cavity pressure increases.

Typical venting-driven failures include:

- Short shots at end-of-fill regions

- Burn marks or black streaks near rib tips and bosses

- Surface scorching in blind pockets

- Inconsistent packing between cavities

- Flash caused by overcompensating with pressure

Each of these defects originates from trapped gas, not insufficient melt flow.

Increasing injection pressure may temporarily push material forward, but it also increases compression heating, flash risk, and clamp force demand. Over time, this approach leads to unstable production rather than a robust process.

Why venting must be finalized before tooling release

Once a mold is manufactured:

- Vent locations are limited to existing parting lines or ejector interfaces

- Increasing vent depth is restricted by material-specific flash limits

- Adding vents often requires EDM, insert replacement, or tool disassembly

At this stage, corrective action results in:

- Tooling rework costs

- Production delays

- Reduced confidence in tool performance

From a DFM perspective, venting must therefore be reviewed and validated alongside gating, wall thickness, and cooling, not after trials expose defects.

Engineering rule of thumb:

If a part fills only at unusually high pressure, venting has not been adequately engineered.

Decision checkpoint:

If venting strategy is not explicitly discussed during DFM, it will reappear later as a production issue.

Share CAD for Mold Venting Risk Review

What Mold Venting Actually Does

To evaluate venting correctly, it is important to understand its role at the process physics level, not just as a tooling feature.

Mold venting exists for one fundamental reason:

To allow trapped air and gases to exit the cavity before they are compressed by the advancing melt front.

Every venting-related defect can be traced back to a failure of this mechanism.

Air displacement during cavity filling

At the start of injection, the mold cavity is filled with air. As molten polymer enters:

- The melt front advances rapidly

- Air is displaced toward end-of-fill regions

- Vents provide controlled escape paths for this air

For filling to remain stable, air evacuation must keep pace with melt advancement. When air cannot escape quickly enough, localized pressure rises ahead of the melt front, causing hesitation or premature freeze-off.

This is why venting issues almost always appear at:

- Terminal flow regions

- Rib tips

- Blind pockets

- Areas opposite the gate

Compression heating and dieseling

When trapped air is compressed, its temperature rises sharply due to adiabatic compression. In injection molding conditions, this temperature can exceed 400–600°C in localized regions.

This leads to:

- Ignition of volatile gases

- Polymer degradation

- Burn marks and surface scorching

This phenomenon, commonly known as dieseling, is not caused by material contamination or overheating of the melt. It is a direct consequence of insufficient venting.

Why increasing pressure makes venting problems worse

A common response during mold trials is to increase:

- Injection pressure

- Injection speed

- Melt temperature

While this may temporarily complete the fill, it introduces new risks:

- Flash due to excessive cavity pressure

- Higher shear heating and material degradation

- Increased clamp force requirements

- Narrower and less repeatable process windows

Key process insight:

Pressure can move molten polymer forward, but it cannot remove trapped gas. In fact, higher pressure intensifies compression heating when venting is inadequate.

Relationship between venting and process limits

Poor venting directly restricts how aggressively a part can be molded.

| Process Variable | Effect When Venting Is Poor |

|---|---|

| Injection speed | Limited by burn mark risk |

| Melt temperature | Raised to compensate → degradation |

| Clamp force | Increased to control flash |

| Cycle time | Extended due to conservative settings |

| Process window | Narrow and unstable |

Properly engineered venting allows:

- Lower peak injection pressures

- Faster, safer fill speeds

- More consistent part quality over production volume

Venting is not an isolated tooling feature

Venting effectiveness depends on:

- Gate location and flow direction

- Wall thickness transitions

- Flow length and cavity layout

- Material viscosity and filler content

- Cooling efficiency and freeze-off timing

Evaluating venting in isolation leads to trial-and-error tuning and repeated mold interventions. Evaluating it during DFM leads to predictable, scalable production.

Decision checkpoint:

If venting strategy is not reviewed together with gating and flow path during DFM, it will surface later as a manufacturing constraint.

Request a DFM + Tooling Feasibility Review

Common Injection Molding Defects Caused by Poor Venting

Venting-related defects are among the most misdiagnosed issues in injection molding. They are often incorrectly attributed to material quality, melt temperature, or machine capability, when the root cause is trapped air that cannot escape the cavity.

What makes venting defects particularly costly is that they:

- Appear late (during trials or early production)

- Are highly repeatable

- Worsen as injection speed or volume increases

Understanding how these defects present helps engineers determine whether venting alone is sufficient, or if geometry or process changes are required.

Short shots caused by trapped air

Short shots associated with poor venting almost always occur at end-of-fill regions, even when injection pressure is increased.

In these cases:

- The melt front stalls due to compressed air

- Localized pressure prevents further flow

- Increasing pressure yields diminishing returns

Typical locations include:

- Rib tips

- Thin wall extremities

- Areas opposite the gate

- Blind pockets and enclosed features

If a short shot improves slightly with higher pressure but never fills consistently, venting is the limiting factor, not flow length alone.

Burn marks and dieseling

Burn marks appear as:

- Black or brown streaks

- Darkened patches near end-of-fill

- Scorched surfaces around ribs and bosses

These are caused by compression heating of trapped gases, not overheating of the melt.

Key indicators that burn marks are venting-related:

- Defects worsen at higher injection speeds

- Lower melt temperature does not eliminate the issue

- Marks appear consistently at the same locations

Inadequate vent depth or poorly placed vents are the most common root causes.

Flash due to overcompensation

Flash is often a secondary defect caused by attempts to compensate for poor venting.

When venting is insufficient:

- Injection pressure is increased to complete fill

- Cavity pressure rises beyond parting line limits

- Material escapes through parting lines or vents

This leads to a false conclusion that:

“The vent depth is too large”

In reality, flash is often the result of too much pressure being used to overcome trapped gas, not excessive venting.

Splay and surface defects

Splay marks (silver streaks) are commonly associated with moisture, but poor venting can amplify the problem by:

- Trapping air mixed with volatiles

- Creating turbulent flow at end-of-fill

- Preventing gases from exiting cleanly

If drying parameters are correct and splay persists near end-of-fill, venting should be reviewed.

Defect-to-root-cause mapping

| Defect | Likely Venting Issue | Typical Fix |

|---|---|---|

| Short shot | Insufficient venting at end-of-fill | Add or relocate vents |

| Burn marks | Vent depth too shallow | Increase depth within material limits |

| Flash | Pressure too high due to trapped air | Improve venting, reduce pressure |

| Splay | Poor gas evacuation | Add vents, review material handling |

| Inconsistent fill | Uneven venting across cavity | Balance vent locations |

Decision checkpoint:

If defects consistently appear at the same locations across trials, venting — not processing — is the primary variable.

Request a Venting-Focused DFM Review

Where Mold Venting Is Mandatory (Geometry-Based Rules)

Ignoring these regions during tooling design guarantees corrective work later.

End-of-fill regions

The most critical venting locations are terminal flow areas, where the melt front stops advancing.

These areas experience:

- Maximum air compression

- Highest risk of burn marks

- Premature freeze-off

Every end-of-fill region should have a planned venting strategy, even if the feature appears minor.

Thin-to-thick transitions

When melt flows from thin sections into thicker regions:

- Flow velocity drops

- Air becomes trapped ahead of the melt

- Packing becomes inconsistent

These transitions require:

- Localized venting

- Careful control of vent land length

Failure to vent these zones often leads to sink, burns, or incomplete packing.

Rib tips and boss bases

Ribs and bosses act as flow terminators, especially when:

- Rib thickness exceeds recommended ratios

- Multiple ribs converge

- Bosses are enclosed by surrounding walls

Common venting-related issues in these areas:

- Short shots at rib tips

- Burn marks at boss bases

- Cosmetic defects around functional features

Vents should be placed at rib ends and around boss perimeters, not assumed to be handled by parting line venting alone.

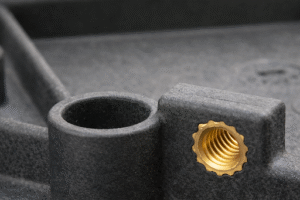

Blind pockets and enclosed volumes

Any feature that creates a dead-end cavity must be vented explicitly.

Examples include:

- Screw boss holes

- Enclosed ribs

- Deep pockets with no through-path

Without venting, these features rely on gas diffusion, which is insufficient at production injection speeds.

Weld line and flow convergence zones

When two melt fronts meet:

- Air can become trapped between them

- Venting helps stabilize weld line formation

- Cosmetic and structural defects are reduced

In high-speed or cosmetic parts, venting near weld lines is often required to maintain consistency.

Geometry-based venting checklist

Venting should be reviewed whenever a part includes:

- Thin walls below 1.2 mm

- Long flow lengths

- Dense rib or boss networks

- Blind pockets or enclosed features

- Multiple gates or flow convergence areas

If two or more of these conditions exist, venting must be explicitly designed and validated during DFM.

Decision checkpoint:

If venting locations cannot be clearly identified from CAD alone, moldability risk is high.

Share CAD for Geometry-Based Venting Assessment

Standard Mold Vent Design Metrics (Material-Based Engineering Rules)

Once venting locations are identified, the next critical decision is how much venting is allowed without introducing flash, cosmetic defects, or material leakage. This is where most tooling mistakes occur — vents are either cut too shallow to function, or too deep to control.

Vent design must always be material-specific, because different polymers tolerate different vent depths before flash occurs.

Core vent geometry parameters

Every mold vent is defined by three parameters:

- Vent depth – controls gas escape vs flash risk

- Vent width – controls evacuation capacity

- Vent land length – controls sealing before melt escape

All three must be designed together. Increasing one parameter without adjusting the others often leads to unstable results.

Standard vent depth guidelines (global benchmarks)

The table below reflects production-proven ranges used across US, EU, and Asian tooling environments. These are starting points, not absolutes.

| Material Type | Typical Vent Depth (mm) | Vent Width (mm) | Land Length (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABS | 0.02 – 0.04 | 3 – 6 | 0.5 – 1.0 |

| PP | 0.02 – 0.05 | 3 – 6 | 0.5 – 1.0 |

| HDPE / LDPE | 0.03 – 0.05 | 3 – 6 | 0.5 – 1.0 |

| PC | 0.01 – 0.02 | 3 – 5 | 0.8 – 1.2 |

| Nylon (PA6/PA66) | 0.01 – 0.02 | 3 – 5 | 0.8 – 1.2 |

| Glass-filled plastics | 30–50% lower than base resin | Controlled | Short |

| Flame-retardant grades | Reduced depth | Narrow | Short |

Engineering note:

Filled and flame-retardant materials require shallower vents due to higher abrasion, fiber blockage, and flash sensitivity.

Why vent depth alone is not enough

Many tooling issues arise because vent depth is treated as the only variable.

In reality:

- A shallow vent with insufficient width may still trap gas

- A deep vent with excessive land length may seal prematurely

- A wide vent without proper land length can flash unpredictably

Rule of thumb:

If venting is ineffective without flash, the issue is usually vent geometry balance, not depth alone.

Regional tooling tolerance considerations

Venting performance also depends on tooling capability:

- High-precision tooling (US / EU): tighter vent depth control, longer land lengths

- Cost-optimized tooling: shallower vents, more frequent maintenance

- High-volume production: conservative vent depths to reduce wear

This is why venting should be reviewed alongside tooling strategy and expected production volume.

When standard venting is insufficient

Standard parting-line venting may not be adequate when:

- Injection speeds are high

- Flow lengths are long

- End-of-fill areas are isolated

- Cosmetic requirements are strict

In these cases, additional venting strategies are required, which are covered in later sections.

Decision checkpoint:

If standard vent depths cannot be applied without flash, redesign or alternative venting methods should be evaluated.

Request Vent Design Validation Before Tooling

Venting vs Material Selection (Decision-Level Trade-Offs)

Material selection has a direct and often underestimated impact on venting effectiveness. Two parts with identical geometry can behave very differently solely due to polymer choice.

Understanding this relationship helps determine whether:

- Venting changes are sufficient

- Process limits will be restrictive

- Geometry redesign is unavoidable

Low-viscosity vs high-viscosity materials

Low-viscosity materials (PP, PE):

- Flow easily

- Tolerate deeper vents

- Are more forgiving of marginal venting

High-viscosity materials (PC, nylon):

- Resist flow

- Trap air more easily

- Require precise vent placement and depth control

As viscosity increases, vent depth tolerance decreases.

Glass-filled materials

Glass-filled polymers introduce additional challenges:

- Fibers partially block vents

- Vent edges wear faster

- Fiber protrusion can create flash paths

For glass-filled grades:

- Vent depth is typically reduced by 30–50%

- Vent width must be carefully controlled

- Maintenance frequency increases over volume

In many cases, venting alone cannot compensate for poor flow path design when using filled materials.

Flame-retardant and additive-heavy resins

Flame-retardant and additive-rich materials:

- Release more volatiles during filling

- Are more sensitive to compression heating

- Increase burn mark risk if venting is insufficient

These materials often require:

- Additional vents at end-of-fill

- Shorter vent land lengths

- Conservative injection speeds

Ignoring venting during material selection often leads to late-stage tooling compromises.

Elastomers vs rigid thermoplastics

Elastomers:

- Trap air more easily

- Require wider venting

- Are more sensitive to vent blockage

Rigid thermoplastics:

- Allow more precise vent control

- Are less tolerant of over-venting

Material behavior must be factored into venting strategy early, especially for mixed-material product families.

When venting cannot solve the problem alone

Venting is unlikely to be sufficient when:

- Extremely high-viscosity materials are used

- Flow lengths are excessive

- Thin walls coincide with filled resins

- Cosmetic requirements are very strict

In these cases, geometry modification, gating changes, or material substitution should be evaluated.

Decision checkpoint:

If vent depth must be reduced below functional limits due to material sensitivity, redesign should be considered.

Get Material-Specific Venting & DFM Review

Venting Locations & Tooling Options

(How venting is physically implemented in real molds)

Once venting requirements are defined by geometry and material, the next decision is how venting will be executed in the tool. This is not a single solution problem — venting strategy depends on part complexity, tooling type, production volume, and maintenance expectations.

In production molds, venting is typically achieved through multiple complementary methods, not a single vent feature.

Parting line venting

Parting line vents are the most common and most economical venting method.

They are typically used for:

- General cavity air evacuation

- End-of-fill regions near parting surfaces

- Simple to moderately complex parts

Advantages:

- Low tooling complexity

- Easy access for maintenance

- Suitable for most unfilled thermoplastics

Limitations:

- Ineffective for deep cavities or enclosed features

- Dependent on parting line location

- Limited vent depth before flash occurs

Parting line venting alone is often insufficient for rib-dense or high-speed molded parts.

Ejector pin venting

Ejector pins naturally create micro-clearances that can be used as vent paths when designed intentionally.

Used for:

- Deep ribs and bosses

- Blind pockets

- End-of-fill regions away from parting lines

Advantages:

- Allows venting deep inside the cavity

- No additional vent machining required

- Effective for complex geometries

Considerations:

- Requires precise pin fit and alignment

- Higher maintenance due to debris buildup

- Less predictable venting than dedicated vents

Ejector pin venting works best when combined with parting line vents.

Sleeve ejector venting

Sleeve ejectors are particularly effective for:

- Circular bosses

- Core pins

- Deep cylindrical features

Advantages:

- Large venting area

- Effective gas evacuation

- Robust for high-speed filling

Limitations:

- Higher tooling cost

- Requires precise machining

- Not suitable for all geometries

Sleeve venting is often used in high-volume or high-speed production molds where reliability is critical.

Valve pin and hot runner venting

In hot runner systems, venting strategy must account for:

- Higher melt temperatures

- Faster filling

- Reduced natural air escape paths

Venting options include:

- Dedicated vents near valve gates

- Venting through ejectors in hot runner cavities

- Supplemental vents at weld line zones

Hot runner molds are less forgiving of venting errors and typically require explicit venting analysis during DFM.

Porous inserts and sintered vents

Porous metal inserts allow air to escape while blocking molten plastic.

Used for:

- Deep blind pockets

- Cosmetic surfaces where vents are unacceptable

- High-risk trapped air zones

Advantages:

- Continuous gas evacuation

- No visible vent marks

- Effective for difficult geometries

Trade-offs:

- Higher insert cost

- Susceptible to clogging

- Requires regular maintenance

Porous inserts should be used selectively, not as a default solution.

Tooling option comparison

| Venting Method | Best Use Case | Cost Impact | Maintenance Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parting line vents | Simple geometry | Low | Low |

| Ejector pin venting | Deep features | Low–Medium | Medium |

| Sleeve ejectors | Bosses, cores | Medium–High | Medium |

| Hot runner venting | High-speed molds | High | Medium |

| Porous inserts | Blind pockets | High | High |

Decision checkpoint:

If venting relies on a single method for a complex part, risk is high.

Request Tooling-Level Venting Strategy Review

Over-Venting Risks (What Not to Do)

While insufficient venting causes fill defects, over-venting introduces a different class of production problems. These are often harder to diagnose because they appear intermittently and worsen over time.

Over-venting is typically the result of:

- Excessive vent depth

- Excessive vent width

- Poor land length control

- Attempting to “solve everything” with venting alone

Flash and cosmetic defects

The most immediate symptom of over-venting is flash.

Flash occurs when:

- Vent depth exceeds material flash limit

- High cavity pressure forces melt into vents

- Clamp force is insufficient to compensate

This leads to:

- Parting line flash

- Feathered edges

- Cosmetic rework or rejection

Flash often worsens as tooling wears, making early over-venting decisions particularly costly.

Material leakage and vent fouling

When vents are too deep or too wide:

- Molten material enters vent channels

- Vents clog over time

- Venting effectiveness decreases progressively

This creates a cycle of:

- Frequent cleaning

- Increased downtime

- Inconsistent part quality

Surface marking and vent witness lines

Over-venting can leave:

- Visible vent marks

- Surface streaking

- Edge deformation near vents

These issues are especially problematic in:

- Cosmetic housings

- Consumer-facing components

- Tight-tolerance assemblies

Tool wear and long-term instability

Excessive venting accelerates:

- Steel erosion

- Edge rounding

- Loss of vent depth control

Over long production runs, this results in:

- Increasing flash risk

- Reduced process repeatability

- Unplanned tool maintenance

Why deeper vents are not a safe fix

A common misconception is:

“If venting isn’t enough, just cut deeper vents.”

In reality:

- Deeper vents reduce sealing effectiveness

- Flash becomes unpredictable

- Tool life decreases

Engineering rule:

Venting effectiveness should be increased by better placement and distribution, not unlimited depth.

Decision checkpoint:

If venting changes introduce flash, the solution is usually redistribution or redesign, not deeper cuts.

Get Expert Review Before Modifying Mold Vent

Venting vs Injection Speed & Fill Profile

(Process window control)

Venting effectiveness directly determines how aggressively a part can be molded. Injection speed, fill profile, and venting are tightly coupled variables — changing one without considering the others leads to instability.

In well-vented molds, injection speed is selected based on part quality and cycle time goals. In poorly vented molds, injection speed is limited by burn risk and short-shot behavior, regardless of machine capability.

High-speed filling and venting limits

High injection speeds are often required for:

- Thin-walled parts

- Long flow lengths

- Cosmetic surface quality

- Dimensional consistency

However, higher speed increases:

- Air compression rate

- Localized temperature rise

- Risk of dieseling at end-of-fill

Without adequate venting, high-speed filling becomes impossible to control.

Multi-stage injection profiles

Modern molding processes often use multi-stage injection profiles, where:

- Initial fill is fast

- End-of-fill speed is reduced

- Packing is controlled separately

Venting must be designed to support the highest velocity stage, not just the average fill rate.

If vents cannot evacuate air during the fastest stage:

- Burn marks appear

- Short shots persist

- Process tuning becomes ineffective

Venting as a pressure-reduction mechanism

Proper venting allows:

- Lower peak injection pressure

- Reduced clamp tonnage

- Improved mold safety margin

In many cases, improving venting achieves the same effect as increasing machine capacity — without hardware changes.

Relationship between venting and process stability

| Condition | Poor Venting | Proper Venting |

|---|---|---|

| Injection speed | Severely limited | Optimized |

| Peak pressure | High | Lower |

| Clamp force | Elevated | Controlled |

| Scrap rate | High | Reduced |

| Process window | Narrow | Wide |

Decision checkpoint:

If injection speed must be artificially limited to prevent burns, venting is constraining the process.

Request Process + Venting Optimization Review

Venting in Complex Mold Designs

(Risk scaling with complexity)

As mold complexity increases, venting risk scales non-linearly. Strategies that work for single-cavity or simple molds often fail when applied to complex tooling.

Multi-cavity molds

In multi-cavity molds:

- Each cavity must vent independently

- Venting imbalance causes cavity-to-cavity variation

- Scrap often appears in only some cavities

Common mistakes include:

- Relying on shared vent paths

- Unequal vent depth across cavities

- Ignoring cavity-specific end-of-fill zones

Balanced venting is as important as balanced gating.

Family molds

Family molds present unique venting challenges:

- Different part sizes fill at different rates

- End-of-fill regions vary by part

- Venting requirements are unequal

Without cavity-specific venting:

- Smaller parts may flash

- Larger parts may short-shot

- Process tuning becomes impossible

Family molds require individual vent strategies per cavity, not a common solution.

Hot runner systems

Hot runner molds increase venting sensitivity due to:

- Higher melt temperatures

- Faster filling

- Reduced natural vent paths

Venting considerations include:

- Dedicated venting near valve gates

- Controlled vent depth to avoid stringing

- Enhanced vent maintenance planning

Hot runner molds tolerate less venting error than cold runner systems.

Stack molds and advanced tooling

Stack molds and complex tooling amplify venting risk because:

- Access to vents is limited

- Maintenance is more difficult

- Venting errors affect multiple parting planes

In these molds, venting must be validated before tooling release, as post-build corrections are costly.

Micro-feature and precision molds

Small features and tight tolerances leave minimal margin for venting:

- Vent depth control becomes critical

- Flash tolerance is extremely low

- Air entrapment risk is high

These molds often require:

- Simulation-supported vent placement

- Conservative material selection

- Higher tooling precision

Decision checkpoint:

If mold complexity increases, venting strategy must be explicitly upgraded — not reused.

Get Venting Strategy Review for Complex Tooling

Vent Maintenance & Tool Life Impact

(What happens after 10k, 100k, 1M shots)

Venting performance does not remain constant over the life of a mold. Even when vents are designed correctly, wear, buildup, and blockage progressively reduce effectiveness. This makes vent maintenance a tool life variable, not a housekeeping task.

Ignoring vent maintenance planning during design leads to:

- Gradual increase in burn marks

- Rising injection pressure over time

- Unexpected flash after initial stable runs

- Frequent, unplanned mold stoppages

Why vents lose effectiveness over time

The most common reasons vents degrade include:

- Carbon and resin residue buildup

- Fiber accumulation in filled materials

- Steel edge rounding due to abrasion

- Material smear into vent lands

These effects reduce the effective vent depth, even though the vent geometry has not visibly changed.

Maintenance frequency vs production volume

Vent design must consider expected shot volume, not just first-article performance.

| Production Volume | Typical Vent Behavior | Maintenance Expectation |

|---|---|---|

| <10,000 shots | Minimal degradation | Visual inspection |

| 10k – 100k shots | Partial vent fouling | Periodic cleaning |

| 100k – 500k shots | Noticeable pressure increase | Scheduled maintenance |

| >500k shots | Progressive blockage & wear | Design-for-maintenance critical |

High-volume molds require vent designs that remain functional under wear, not just optimal on day one.

Impact of material choice on vent maintenance

Material selection significantly affects vent longevity:

- Glass-filled materials accelerate vent wear

- Flame-retardant grades increase residue buildup

- Elastomers clog vents faster than rigid plastics

For abrasive or additive-heavy materials:

- Vent depths should be conservative

- Vent widths should allow cleaning access

- Maintenance intervals should be defined upfront

Failing to account for this often results in vent re-cutting or insert replacement mid-production.

Vent maintenance vs process drift

As vents clog:

- Injection pressure must be increased to maintain fill

- Clamp force requirements rise

- Process window narrows

These changes are often gradual, causing teams to “chase settings” instead of addressing the root cause.

Engineering insight:

If injection pressure creeps upward over time for the same part, vent degradation should be investigated before adjusting process parameters.

Designing vents for maintainability

Production-ready venting strategies include:

- Accessible vent locations

- Replaceable vent inserts where feasible

- Vent geometry that tolerates minor wear

- Clear maintenance documentation

Venting that cannot be cleaned or restored easily becomes a long-term production liability.

Decision checkpoint:

If vent maintenance requirements are not defined during tooling design, tool life risk is high.

Request Tool Life–Focused Venting Review

Venting vs Cooling vs Gating

(Choosing the correct corrective lever)

Many injection molding defects can be influenced by multiple design levers. Misidentifying the primary lever leads to ineffective fixes and repeated tool changes.

This section helps engineers determine when venting is the correct solution — and when it is not.

When venting is the right fix

Venting is the primary corrective lever when:

- Defects appear at consistent end-of-fill locations

- Burn marks worsen with higher injection speed

- Short shots persist despite sufficient flow capacity

- Pressure increases do not stabilize filling

In these cases, improving vent placement or geometry often resolves the issue without modifying part design.

When cooling changes are more effective

Cooling is the dominant lever when:

- Warpage dominates over fill issues

- Sink marks occur in thick sections

- Dimensional variation increases with cycle time

Cooling adjustments will not resolve:

- Burn marks

- Trapped gas short shots

- Compression heating defects

Attempting to fix venting problems through cooling changes usually wastes time.

When gating must be reconsidered

Gating changes are required when:

- Flow length is excessive

- Weld lines occur in functional areas

- End-of-fill regions are unavoidable due to gate placement

In some cases, poor venting is a symptom of poor gating, not the root cause.

Trade-off decision matrix

| Problem Symptom | Venting Fix | Cooling Fix | Gating Fix |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short shots at end-of-fill | ✔ Primary | ✖ | ✔ Sometimes |

| Burn marks | ✔ Primary | ✖ | ✖ |

| Flash | ✔ Secondary | ✖ | ✖ |

| Warpage | ✖ | ✔ Primary | ✖ |

| Sink marks | ✖ | ✔ Primary | ✖ |

| Weld line weakness | ✔ Secondary | ✖ | ✔ Primary |

Avoiding the “wrong lever” trap

The most common mistake in tooling correction is:

Applying the easiest change, not the correct one.

Venting, cooling, and gating must be evaluated together during DFM to avoid:

- Multiple mold reworks

- Conflicting design changes

- Delayed production readiness

Decision checkpoint:

If multiple fixes are attempted without improvement, the wrong lever is being pulled.

Get Corrective Strategy Review (Venting vs Cooling vs Gating)

Mold Venting DFM Checklist

(Pre-tooling validation — engineering sign-off)

This checklist is designed to be used before tooling release, not after trial failures. Each item addresses a known venting-related failure mode observed in production molds.

If multiple items cannot be confidently checked, venting risk is high.

Geometry-based venting checks

Confirm that:

- All end-of-fill regions are identified from flow direction

- Rib tips and boss bases have explicit venting paths

- Thin-wall extremities (<1.2 mm) are vented

- Blind pockets and enclosed volumes are not relying on diffusion

- Weld line zones have planned gas escape paths

If venting locations cannot be clearly marked on CAD, DFM review is incomplete.

Material-based venting checks

Confirm that:

- Vent depth matches material flash limits

- Filled or flame-retardant materials use reduced vent depths

- Additive-heavy materials have additional venting allowance

- Elastomers or soft plastics are not under-vented

Material selection must be validated together with vent geometry, not independently.

Tooling execution checks

Confirm that:

- Venting is not limited to parting lines alone

- Deep features use ejector or sleeve venting

- Vent land length is controlled and consistent

- Vent access for cleaning is planned

- High-risk zones do not rely on a single venting method

Single-point venting in complex geometry is a common tooling failure.

Process compatibility checks

Confirm that:

- Venting supports maximum planned injection speed

- Venting does not require excessive clamp force

- Process window is not dependent on reduced speed to avoid burns

- Venting performance does not rely on elevated melt temperature

If the process only works under “gentle” conditions, venting is marginal.

DFM sign-off rule:

If more than two checklist items are uncertain, venting must be reviewed before tooling release.

Request Mold Venting DFM Sign-Off

Venting Readiness Score

(Quantifying venting risk before steel is cut)

The Venting Readiness Score converts qualitative venting risk into a numerical decision aid.

Each category is scored from 0–20.

Scoring categories

| Category | Score Range | Evaluation Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Geometry risk | 0–20 | End-of-fill, ribs, blind pockets |

| Material risk | 0–20 | Viscosity, fillers, additives |

| Tooling strategy | 0–20 | Vent types, access, redundancy |

| Process demand | 0–20 | Injection speed, pressure |

| Maintenance readiness | 0–20 | Wear tolerance, access |

Interpreting the score

| Total Score | Venting Status | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| 80–100 | Tool-ready | Proceed to tooling |

| 60–79 | Toolable with risk | Review venting before release |

| 40–59 | High risk | Vent redesign required |

| <40 | Not tool-ready | Geometry/process changes needed |

This score helps engineering teams justify venting changes internally before tooling cost is committed.

Decision checkpoint:

If venting readiness is below 80, tooling risk increases sharply.

Get Venting Readiness Score from Manufyn

Worked Example – From Venting Failure to Stable Production

Part overview

- Material: Glass-filled nylon

- Geometry: Rib-dense housing with blind bosses

- Wall thickness: 1.4 mm nominal

- Tooling: 2-cavity cold runner mold

Initial production issues

- Short shots at rib tips

- Burn marks near enclosed bosses

- High injection pressure required to fill

- Frequent process adjustments

Root cause analysis

DFM review identified:

- No vents at rib ends

- Blind bosses relying on parting line venting

- Vent depth too shallow for trapped gas volume

- Injection speed exceeding vent evacuation capacity

The defects were venting-driven, not material-driven.

Corrective actions

- Added vents at rib tips and end-of-fill zones

- Introduced ejector pin venting for blind bosses

- Optimized vent land length

- Reduced injection speed after venting improvement

No geometry changes were required.

Production outcome

- Short shots eliminated

- Burn marks removed

- Injection pressure reduced by ~18–22%

- Clamp force reduced

- Stable process window achieved

Tool modification cost was significantly lower than ongoing scrap and downtime.

Engineering takeaway:

Venting correction early is exponentially cheaper than fixing defects after production begins.

Request Venting Failure Analysis for Your Part

Mold Venting vs Full DFM

(Where venting analysis ends — and where full DFM begins)

Mold venting analysis addresses air evacuation and gas-related failures, but it is only one component of a complete Design for Manufacturability (DFM) review.

Understanding this boundary is critical to avoid:

- Incomplete tooling decisions

- Over-fixing venting when the root cause lies elsewhere

- Late-stage redesigns after tooling investment

What mold venting analysis covers

Venting-focused review evaluates:

- End-of-fill air entrapment risk

- Vent placement and geometry

- Material-specific vent depth limits

- Interaction with injection speed and pressure

- Maintenance and tool life considerations

If defects are caused by trapped gas, venting analysis is often sufficient to resolve them.

What venting analysis does NOT cover

Venting analysis alone does not address:

- Wall thickness uniformity

- Draft angles and ejection risk

- Cooling channel efficiency

- Gate location optimization

- Warpage and shrinkage control

- Dimensional tolerance stack-up

Attempting to solve these issues through venting adjustments leads to repeated tool modifications without stability.

When full DFM is required

A full DFM review is recommended when:

- Multiple defect types appear simultaneously

- Geometry-driven flow limitations exist

- Tolerances are tight or functional

- Material selection is still flexible

- Production volumes are high

In these cases, venting must be evaluated as part of the complete molding system, not in isolation.

Decision checkpoint:

If venting fixes improve defects but do not stabilize production, a full DFM review is required.

Request Full Injection Molding DFM Review

Mold Venting Services by Manufyn

(Engineering execution, not advisory)

Manufyn provides venting-focused tooling and DFM services as part of its injection molding execution capabilities. These services are designed to eliminate venting-related failures before tooling release or during controlled mold optimization.

Venting-related services offered

Pre-tooling venting feasibility

- CAD-based venting risk assessment

- End-of-fill identification

- Material-specific vent recommendations

Tooling vent design

- Vent location and geometry definition

- Selection of venting methods (parting line, ejector, sleeve, inserts)

- Tool-ready vent drawings

Mold modification & rework

- Controlled vent additions

- Vent depth optimization

- Insert-based venting solutions

Process optimization

- Injection speed and fill profile alignment

- Pressure and clamp force reduction

- Venting validation during trials

Global manufacturing support

- Tooling and production support across US, UK, EU, UAE, and India

- Venting strategies aligned to regional tooling standards

When teams engage Manufyn for venting

Clients typically engage Manufyn when:

- Parts fail due to short shots or burn marks

- Tooling rework costs are escalating

- Production windows are unstable

- New tools must be validated before steel is cut

Manufyn’s role is not to recommend — it is to execute and stabilize production

Final Engineering Takeaway & CTA

Mold venting failures are predictable, preventable, and expensive when discovered late.

Validating venting before tooling release reduces:

- Scrap

- Tool rework

- Launch delays

- Long-term process instability

If air cannot escape, plastic cannot flow — reliably or repeatably.

Get Your Mold Venting & DFM Review from Manufyn

FAQs – Mold Venting

What is the ideal vent depth for injection molding?

Ideal vent depth depends on material. Typical ranges are 0.02–0.05 mm for unfilled plastics and 30–50% lower for filled or flame-retardant grades.

Can poor venting cause flash?

Yes. Poor venting often leads to higher injection pressure, which can force material into parting lines and vents, causing flash.

Are vents required in hot runner molds?

Yes. Hot runner molds are more sensitive to venting errors due to higher melt temperatures and faster filling.

How often should mold vents be cleaned?

Cleaning frequency depends on material and volume. High-volume or filled materials may require scheduled cleaning to maintain vent effectiveness.

Can venting replace design changes?

Venting can solve gas-related defects, but it cannot compensate for poor wall thickness design, excessive flow length, or inadequate gating.

What problems are caused by poor mold venting?

Poor mold venting commonly causes short shots, burn marks (dieseling), flash due to over-pressurization, splay, inconsistent cavity filling, and frequent mold maintenance due to vent clogging.